After several high-stakes responsible-tech applications and helping my daughters through college applications, I finally took a Monday off. Sauna. Cold plunge. Steam. Massage. Except…everywhere the blue light from screens stole the stillness. Signs on the changing room doors banned phones; guests had signed waivers agreeing to it; steam rooms could damage devices. None of it mattered. I counted 26 of 29 people on their phones—while paying to escape them.

This is the core problem. We are wrapped in a blanket of addictive tech, across devices, apps, schools, workplaces, homes, and even spas. It shouldn’t be surprising that when the dominant revenue model pays for attention, systems will be optimized to pull us back in, regardless of context.

Follow the Money

If your bottom line grows when people stay online longer, you won’t dedicate real resources to helping them log off. The ad market surpassed $1 trillion in 2024, with digital channels accounting for roughly three-quarters of all ad spending globally, concentrated in platforms designed to monetize time-on-site and data extraction. (Reuters)

- Meta’s 2024 10-K reports $160.6B of $164.5B (~97.6%) from advertising. SEC

- Alphabet reported $264.6B in Google advertising on $350.0B total (~75.6%) in 2024. SEC

When revenue, stock prices, and employee incentives hinge on ads sold, data exchanged, and minutes captured, “engagement” becomes a proxy for success—even when it conflicts with human flourishing. The business model is doing exactly what it was designed to do.

Why regulation alone won’t fix it

My spa day shows how rules and interventions struggle against incentive-aligned design: even in a sanctuary with no-phone signs and privacy concerns, people default to the dopamine loop. The same dynamic plays out in schools experimenting with phone-lock pouches or no-phone policies: they can help, but they’re always fighting uphill against product economics built for attention, demonstrating the futility of limits and regulations without incentive change. (NPR covered the growing “lock up your phone” movement; WNYC profiled the debate directly.) (Vox, WNYC)

Regulators are pushing—rightly. The U.S. Surgeon General has called for warning labels, transparency, and design changes, saying we cannot yet conclude social media is “sufficiently safe” for kids. The FTC has documented “dark patterns” that nudge or trap users. But enforcement lags innovation and legislatures, penalties become a cost of doing business, and design workarounds proliferate. Parents and advocates who’ve testified in Washington, including engineers-turned-whistleblowers, have made this clear: policy sets boundaries, but business models set direction. Unless we change how value is measured and paid, we are rearranging incentives around the same objective: more minutes, more impressions. (HHS, FTC, Surgeon General)

People don’t design products that harm themselves.

Common sense, yes—but also how resilient systems behave when control and consequences are aligned. Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom showed how communities sustainably govern shared resources when users help write and enforce the rules—what she called “rules-in-use.” When people live with the outcomes, they choose protections. (NobelPrize.org)

Health and tech research point the same way: Community-based participatory research improves real-world adoption—better recruitment, retention, and relevance—precisely because those affected co-design what gets built. In youth digital mental health, systematic reviews find engagement hinges on tailoring to young people’s needs and contexts. If you were designing your own car, you wouldn’t place the brake pedal out of reach “because it’s exciting.” When the people who bear the risks are true builders with decision rights, products tilt toward safety. (PMC, JMIR)

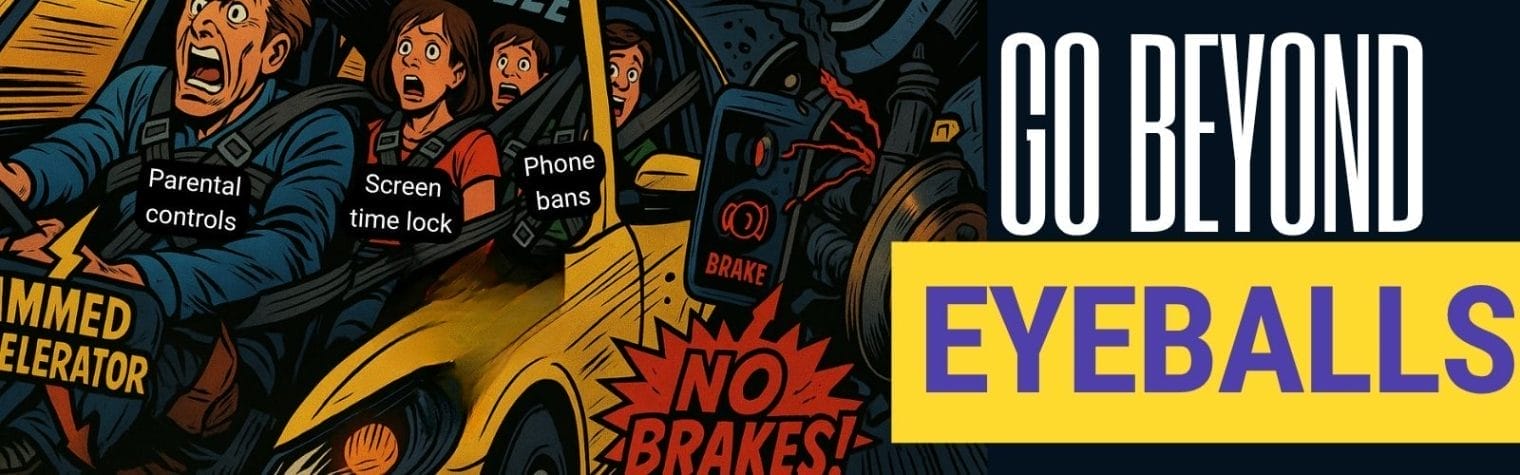

Tools that merely restrict access don’t transfer power; they’re like putting seatbelts on a car with a jammed gas pedal. I’ve tried the full gamut of “digital wellness” products over the last decade—lock pouches, blockers, monitoring. They can buy breathing room, but they don’t change the incentives that keep pulling us back. If people design safer systems when they hold power, then the product must transfer power to the people who live with the consequences and tie revenue to the outcomes they care about. That’s the core of curaJOY’s circular impact model.

What an outcomes-based model might look like

If we want different behavior from tech companies, we must incentivize different outcomes. Move beyond CPMs and MAUs toward value measured in learning, health, and social connection. Here are some suggestions.

1) Define and publish auditable outcomes. Examples: improved teen sleep regularity; reduced school absences; successful mastery of social-emotional skill milestones; fewer online safety incidents. These benefit users, not just dashboards.

2) Tie revenue to outcomes, not minutes. Replace “time spent” targets with service-level objectives around well-being milestones. If a product helps a student meet an IEP or helps a parent de-escalate conflict at home, that is billable value, whether it took five minutes or fifty.

3) Give communities a builder role, not a survey link. Youth, parents, educators, and clinicians should co-author features, reinforcement schedules, and escalation paths. That co-design isn’t a “nice-to-have”; it’s how you avoid predictable harm and earn durable adoption. PMC+1

4) Align incentives across the ecosystem. If schools, clinics, and families are accountable for outcomes (attendance, stress reduction, conflict resolution), vendors should be too.

Building With (Not For) Families: Our Incentive Design

At curaJOY, we’ve been building toward this for years: a circular model that aligns all participants in learning and behavioral support—backed by clinician supervision and community co-creation.

- Community-built content & AI coaches. Youth, parents, educators, and clinicians co-create the skills, interfaces, stories, and guardrails that power our clinician-supervised AI coaches.

- Outcome-linked quests. We reinforce real-world goals, sleep routines, emotion regulation, progress toward IEP, de-escalation, and self-advocacy, rather than time-on-app.

- Transparency & safety triggers. We flag harmful content, poor experiences, or risk indicators for human review and support, and we instrument to learn what actually helps people complete the journey—not just start it.

- Circular rewards. Youth and families earn recognition and, where appropriate, tangible rewards for completing well-being milestones.

This breaks with the attention economy. It redefines what the business gets paid for, and introduces an achievable and sustainable pipeline for more responsible technologists.

Can It Scale?

Attention scales because it’s easy to meter and sell. GroupM projects advertising to comprise ~73% of all digital advertising. Even challengers like Snap have historically derived ~91%+ of revenue from advertising. If we keep paying for time, we’ll keep getting addictive designs. (Reuters)

Scale ≠ value, and in a culture that celebrates bigger, faster, cheaper, not everything should scale—love doesn’t. What we scale are methods and accountability, not the human parts. If scale proved safety, the Surgeon General wouldn’t still be calling for warning labels and evidence standards. Pay for sleep, balance, skills, and conflict-resolution, and you’ll get design patterns that make those more likely, and solutions that would be willing to let people step away when they’ve achieved what they came for.

What leaders can do now?

- Procure for outcomes. Schools, health plans, grantmakers, and employers can write contracts that pay for validated improvements in well-being, not usage.

- Insist on co-design. Make community governance and youth participation a contractual requirement with documented decision rights.

- Demand transparency. Require public safety dashboards and third-party audits.

- Reward time well-spent and well-ended. Build bonuses for designs that help users complete a task and step away.

- Fund the transition. Moving from attention to outcomes takes upfront investment, especially to upskill communities as builders. That’s not overhead; it’s the moat.

This shift away from our attention economy is scary. I’ve learned this the hard way since 2021: building with communities is slower and costlier upfront, but it’s the only way the bucket stops leaking. We don’t have to accept a default where human attention and data are strip-mined because it’s the easiest thing to sell. When the people who live with the consequences are empowered to design the system, and when revenue depends on their thriving, products evolve toward health, not compulsion. That’s how communities have governed shared resources for generations. It’s how we’ll build technology worth handing to our kids. If we want different results, we have to take this leap.

Leave a Reply