My parents are wonderful, and our family is harmonious — this is how most people view our family. “You are an independent child who needs no worrying over”, my parents would say about me. My mother would often recall the days after I was born after she commented on this feature; unlike other babies, I did not cry incessantly but would suck on my fingers and watch them quietly. Once, in our old house, I found my mother’s diary where she wrote unlike others, she always slept well during my infancy.

Unsurprisingly, my parents, like every traditional Chinese parent, expected me from a young age to deliver toasts during festivals and to compliment every unfamiliar relative. If I failed, they would openly criticize me, saying, “This child only excels in academics but lacks social grace. She will face hardships in society.” Predictably, I was the epitome of the “excellent Chinese child.”

To maintain the label of being independent and excellent, I became a child who “tells only the good, not the bad.” My parents always tried to impart life lessons during dinner, telling me I was not good enough. Since I was independent, I should handle all my emotions alone. Gradually, I stopped sharing anything about school with them as they would find faults even in my amusing stories, ending with my tears mixed in my dinner.

They knew I was under great pressure. Being a teacher’s child, there were always rumors at school that I received special treatment from other teachers; if I wasn’t among the top students, it meant I was a fool. In Chinese schools, being the best academically is a popular norm. I cared about others’ opinions, wanting everyone to like me, and I began to “enjoy” being popular.

—

Gaining good grades became a vital part of my life as I had no other way to gain attention and affection. My parents never praised me but would belittle me at the dinner table. In high school, I missed a week of classes due to a study trip to Japan, missing crucial physics lessons on electromagnetic induction that were emphasized heavily in college entrance exams. Returning to school, I faced a pile of assignments on my desk.

Soon, I realized I could see the teacher’s mouth moving, but I could not understand a word. My emotional state deteriorated, and when I told my parents, they dismissed it as me being peculiar and said I just needed to catch up on missed work. I always ended up crying while listening to them, and my rice, of course, mixed with tears.

When I finally tried to explain my emotional breakdown, my parents asked me to consider how sad they were. They said they were comforting me by suggesting I attend a local university so I could come home for dinner. When I asked if they knew what I wanted, my father, who had taught for over a decade, retorted, “Don’t I know what kind of student you are?”

At that moment, I realized I was just an academically excellent, socially awkward, rebellious high schooler. The night I couldn’t eat, anxiety and somatization slipped in. My body trembled, my heart pounded, and I was drenched in a cold sweat; at three in the morning, crying, I knocked on my parents’ bedroom door. The conversation that followed was a blur, but I felt as if I had cried out all the tears of my lifetime. My father let me sleep next to my mother while he took my bed. Lying beside her, I heard her weary sigh; it was turning dawn, and soon she would have to manage the morning reading session at school, and I felt ashamed.

From then on, I could never sleep for more than an hour. Till now, whenever I faced an important exam or interview, sleep eluded me. At school, I became hypersensitive to sounds. Any slight noise would trigger my rapid heartbeat. I always felt exhausted, and my brain resisted memory. Whenever I had the time on weekends, I would spend the whole day lying in bed. Meanwhile, the pain during my menstrual cycle was so intense that I vomited everything in my stomach. My classmates helped me home, watching me collapse on the school playground, hardly looking human. My father rushed to me, carrying me on his back, and I said, “Dad, am I dying?”

“It’s okay. You’ll be fine soon. We’re almost home.” He replied gently.

My parents started taking turns bringing me to various doctors—cardiologists, gastroenterologists, gynecologists—as if we had undergone every possible medical test. Then we finally visited a psychiatrist and got the diagnosis. Holding the diagnosis felt like finding the correct answer to the hardest math problem.

I didn’t tell my classmates or even my teachers about this, as mental illness is a taboo topic in China. One evening, as I tried to maintain silence during a math self-study session, I received a note saying, “With such poor grades, who are you to tell us to be quiet? You’re just a clown.” Then, in front of everyone, I ran out and hid in the bathroom, crying.

— Due to my anxiety, I became desperate for love and companionship, any form of love that asked for nothing in return. My parents couldn’t say it out loud; they were too busy and tired, and I was too independent. I could take care of myself, but medication couldn’t alleviate everything. I had never been taught how to ask for love.

Unresolved emotions became the fuel for reading and writing; I devoured French literature and modern Chinese collections. I began writing fan fiction and quickly amassed fans. The characters I liked always possessed gentleness a touch of madness, and self-destructiveness. My fans were generous with their praise, something I hadn’t heard in over a decade; they looked forward to my next piece, empathized with the characters, or simply admired my work.

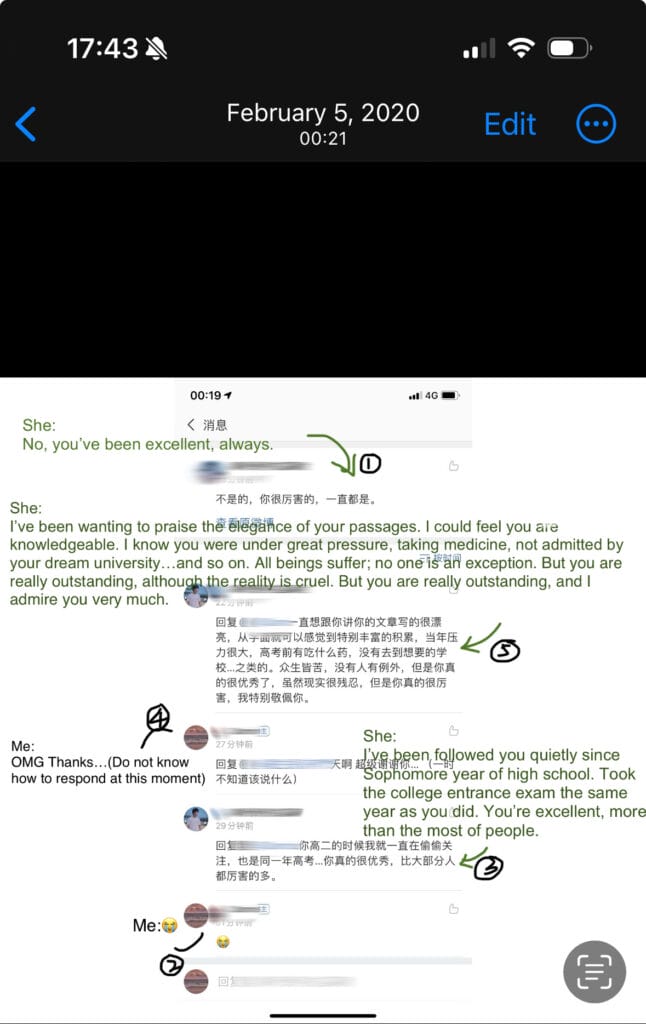

As expected, I did not do well in the college entrance exam, though by others’ standards, it was still an excellent university. One day, I wrote down on Weibo (China’s Twitter), ranting and negating myself, but received comments from a follower:

All beings suffer; no one is an exception. I took a gap year and switched from economics to computer science because coding put me in a rare state of flow. With only three hundred lines of code written, I entered Carnegie Mellon University for studies. Despite the prestigious background, my anxiety rebounded, accompanied by eating disorders and a significant weight gain. After graduation, I faced a rough job market. After consoling my parents that I would find a job soon, I broke down crying in front of the online hiring posts on Chinese New Year’s Eve.

—

I would like to defend my parents for one thing — my anxiety is not all their fault. Nobody is trained to be a parent. They are just path independent, getting along with their daughter like the way with students.

I got bullied for being an “aggressive” girl without a solid grade. After the note issue, I heard more rumors about me. The head teacher doesn’t care about mental health at all. He told me that I had taken too many sick leaves. He also asked my deskmate, the first-ranking student in the entire grade, secretly whether I influenced him. My deskmate told me the conversation without reservation after getting back from the head teacher’s office.

My parents are supportive in other aspects compared to my sufferings at school. I’m lucky enough to get materially privileged than those who have no chance of getting educated not to mention studying abroad. In my parents‘ eyes, I seemed good at handling emotions. But all of a sudden, I erupted like an active volcano. My mom said I was acting weird in the last year of high school. I know she was resisting my diagnosis and numbing herself. It’s hard to imagine that your perfect daughter suddenly turned into one who had insomnia all night and shed tears all day long.

The turning point happened during my graduate study. My mom called me without any schedule in advance. She told me that her teaching assistant committed suicide this morning at home. As a middle school Chinese teacher, she could see no signs. Her voice was trembling. She said, “Take care of yourself. Your mother will always be your side.”

—

My name, Yongxi, means happiness and joy in Tibetan, reflecting the simplest wishes of a parent for their child, but it seems to run counter to the trajectory of my life.

Can a long illness turn one into a doctor? This old Chinese saying isn’t an absolute truth. But if possible, if there are others out there troubled by the same symptoms, I would reach out without hesitation.

Breathe in, breathe out, yes, deep breaths. Perhaps I cannot fully understand your situation, but I know how rough, how long, how trembling, how cold these nights can be, as if snowflakes in the dark sky will never fall, and the sunrise will never come. But I will be with you. Happiness is not a fruit. It cannot ripen. It cannot be grasped. It is a gift that is always there, and it takes a lot of time in the dark to unwind the tangled ribbons. Fortunately, we still have a lot of time to waste, from ancient times to the present, and the future.

Leave a Reply